In this episode, we explore how growth occurs as a constant thread of small changes

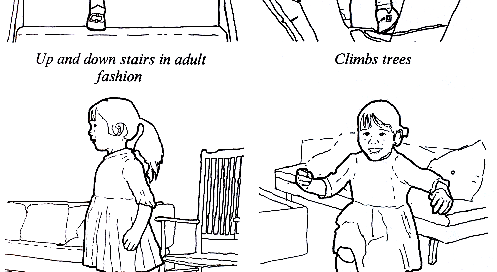

Half a century ago now, one of my first jobs was in working as an illustrator for Mary Sheridan, one of the great pioneers in child-development studies in the mid- to late-20th century. I did quite a few books for her, of which perhaps the most important and influential was her ‘Children’s Developmental Progress': From birth to five years - the STYCAR Sequences’ (NFER, 1972):

(The book became one of the standard reference-works for the entire field: it’s still in print, though the current edition uses ‘updated’ illustrations.)

I learnt a huge amount from Sheridan, about change, about social-stereotypes and gender-stereotypes, about untested assumptions, about the dangers of ‘policy-based evidence’, and much, much more. But perhaps the one theme that’s stuck with me most was about how child-development actually works.

Before she first published her work, from the 1940s onwards, it was assumed that all children should develop in the exact same way. Which, yes, they sort-of do - but not in the simplistic sense that had been presumed, where ‘normal’ should align exactly with ‘the average’.

Instead, Sheridan had split the processes of development into four broad categories: posture and large-movement, vision and fine-movement, hearing and speech, social-behaviours and play. For each age-group, we could identify the typical or average capabilities for each of those categories, and every child would need to go through each of those ‘stepping-stones’ to each normal development. In that sense, it was perhaps technically true that every child was the same. Yet every child was also different: each would need to pass through each of those stepping-stones, yes, but each in their own way. In a ‘normal’ development, at any given moment, the child’s own development would actually match the average in only one of those categories: for the others, that typical child would be one step ahead of the average in one category, and one step behind the average in the other two. It didn’t matter which the respective categories were, as long as that pattern was there: only if the pattern was significantly different, or if the child had skipped over one of the stepping-stones, would any alarm bells need to sound.

And the whole process was completely dynamic: a myriad of small changes, day by day, hour by hour, maybe even minute by minute. Sometimes a child might seem to be worrying late in some aspect of development, but then zoom straight past to a whole new level all in one go. On occasion, a child might even regress, or move back, for no apparent reason - but then show that, like a mountain-climber, had done so to find a new direction to tackle some difficult change, a new route onward and up. Always sort-of the same, but also never quite the same, and sometimes quite profoundly different - yet, whichever route it might take in detail, still always driving in the same overall direction.

“If ever you want to see a miracle”, Sheridan once said to me, “watch a five-year old child on her first day going to school. She may be excited, maybe shy, maybe even a little bit scared of this new thing she’s about to do. Yet already she can walk and run, she can speak and interact with others, she is herself, she has her own ideas and thoughts, her own way of being in the world.” Yes, a miracle indeed, in its own ordinary-seeming way: a huge, huge change in capability, autonomy and more, each child unique. And yet all of this built upward from nothing at all, via this long, subtle sequence of small changes.

The same applies to so many other areas too: in almost every case, a big-change will arise through a myriad of small-changes - rarely just the big-change on its own. And as with child-development, there’ll often be a pattern behind all of those small-changes - a structure of stepping-stones and the like, and dynamic pathways between them, each element and interdependency giving rise to its own unique blend of same-and-different, of ‘local distinctiveness’ and more. So whatever change we’re facing, look for the small-changes, and the patterns that underpin them - because it’ll be there that the choices we need are most likely to be found, to help us navigate the big-changes that we face.

Great article as always Tom, the issue that I have always had with the use of "Normal" in this case is if a child with above average intelligence feels no attraction to the syllabus he / she would be seen as below "Normal" due to his / her reluctance to engage. The individuality of a child has all but disappeared after a few years of meeting the educational "norm". If we are to promote innovation as the way forward small changes can lead to the big change we need in how we approach education for the learning experience of children.