In this episode, we explore what happens when an untested or invalid assumption collides with Reality Department

The piece of fabric that Norway’s colleague had handed him crumbled into pieces in his hands. In moments, there’s nothing left but small flecks of dust.

“It’s an aircraft-fabric, isn’t it? Which aircraft is this from?” Norway asks, in concern. “What made it this friable?”

“It’s from the R101”, replies his colleague. “It’s the new coating they’re using on the airship’s gas-bags. They haven’t tested it at all, they’ve just assumed it’ll be fine. And they’ve issued the Certificate of Airworthiness yesterday, because the Air Minister insists he wants to fly on it to Karachi next week.”

Norway looks up at his colleague in horror.

The Air Minister never did get to India. Instead, along with almost everyone else on on board, he died in France, only a short way into that flight…

That story comes from Slide Rule, the early-years autobiography of Nevil Shute Norway, who was working at the time as a design-engineer on the competitor-airship R100. (He’s better known for his later career as a novelist, under the pen-name Nevil Shute.) And that self-disintegrating fabric was only one amongst several other lethally-dangerous untested-assumptions that contributed to that fatal crash.

We might hope that that industry would have learned its lessons there about the dangers of refusing to face untested-assumptions, wouldn’t we?

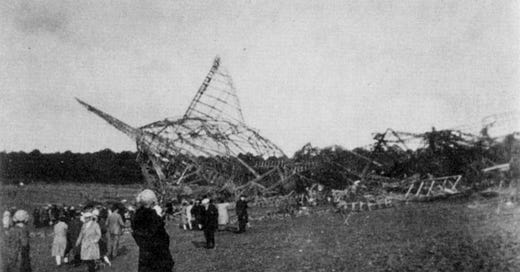

But no, some thirty-five years later, almost exactly the same kinds of issues led to this…

Leaving assumptions untested - or worse, refusing to face the fact when they have been tested and shown to be invalid - is most definitely Not A Good Idea…

And whilst it’s bad enough in technology - as in those examples above - it’s even worse in the social sphere, where the hidden assumptions are hard to find, and even harder to test and to address.

But what can we do about it?

What can we do about it? Quite a lot, actually.

The first point is to give it a name, so that we can talk about it in a meaningful way. To me, there there are two parts to this: identify what we’re dealing with here, and then what’s going on.

What we’re dealing with is assumptions - each a prepackaged decision about what’s real and what’s not, or a right or wrong way to work with the world. Since an assumption has no means within itself to test whether it’s valid or not, then until it’s and validated for the respective conditions it’s basically just a myth - a description of an imagined world.

What goes on when an assumption fails is that there’s a mismatch between the real world and the imagined world of the myth. This creates cognitive dissonance, the psychological, emotional and/or spiritual equivalent of an earthquake - a quake that disrupts the personal world.

In short, what we get when an untested or invalid assumption collides with Reality Department is a mythquake.

There are some mythquakes we’d want, of course: mythquake as opportunity. For example, the mythquake that occurs - or rather, must occur - to create a shift from “I can’t do this” to “I can do this!” when learning each new stage of a skill. Or the kind of mythquake that occurs sometimes in the sciences, such as Alexander Fleming’s insight that an unexpected mould in a petri-dish might mean something useful - leading to the development of antibiotics that save millions of lives each year.

Most mythquakes, though, are more on the risk side of the risk/opportunity equation, as seen as in those earlier examples. But despite Feynman’s warning at the end of his report on the Challenger disaster, that “Nature cannot be fooled”, people can be fooled - or, perhaps more often, fool themselves. See, for example, the exchange from 5:35 onwards in this clip from HBO’s Chernobyl mini-series: technician Sitnikov tries to explain to the managers that the dosimeter “maxed out” at a reading of 200 Roentgen, a potentially-lethal dosage. One of the managers says, “It’s another faulty meter, you’re wasting our time”. Sitnikov explains that the meter can’t be faulty, and that he thinks there’s radioactive graphite amongst the rubble on the ground; manager Dyatlov yells at him “You didn’t see graphite! You didn’t! It’s not possible! Because it’s not there!” But in fact, the graphite was indeed there; and we know from earlier that Dyatlov himself has seen it, but cannot admit to himself that he has. The managers are so desperate to pretend that nothing is wrong that they force Sitnikov, at gunpoint, to go out onto the balcony and look directly down into the ruined reactor core, to report back what he sees there; the radiation level is so high that it kills him only a few days later. (True, the scene is in part fictionalised, but it conveys all too well the managers’ literal refusal to face the facts.)

When people fool themselves or others about things that matter, and insist on continuing to do so even when they’re shown that they’re wrong, things can go very badly wrong indeed…

When the earth moves, we call it an earthquake; when myths move, we have a mythquake. There’s an almost exact analogy here of seismic forces in the social soul: teleology as geology, psychology as seismology. At the surface there are everyday upsets; but deeper, far deeper, are tectonic plates of ideas, assumptions, myths, beliefs. Stories. So what happens, then, when the mythic ground beneath our feet slips, slides, jolts, moves? When stories collide? That’s what we’re dealing with here.

In essence, the real issue here is about assumptions - ones that are either unknown, unacknowledged, untested or, in some cases, known to be invalid or wrong but fiercely defended anyway. And again in analogy with earthquakes, the real danger here is not so much the assumption itself, but the structures that we build upon those unstable foundations. So in the same way that we need earthquake-preparedness, and similar risk-management for all those other types of natural-disasters, we also need proper ‘mythquake preparedness’ to manage the equally-real risks from these potential cognitive-disasters.

We’ve tackled the first part: we know what we dealing with, namely misplaced assumptions. We now have a name for what we’re dealing with, namely mythquake. And we have some idea of how we’re going to tackle these issues, namely by surfacing these misplaced assumptions, by testing their validity once they’ve been surfaced, and by challenging them as necessary. That part at least is straightforward - or relatively straightforward, anyway…

Yet there’s one more catch we need to face here, in order to properly assess and address the mythquake-risk: and that’s that the potential intensity of a mythquake increases the more that people refuse to face the reality that their assumption is invalid - that it’s literally just a myth. For that, we’re going to need some means of identifying and measuring the risk - a mythquake-scale, in the same sense that we have a scale to identify and measure earthquake-risk and earthquake-impact. But I’ll talk about that more next week; for now, we have enough to at least get started on tackling the challenge of mythquakes.

Great read! I like the word "Mythquake "and the way its definition explained with great examples.