In this episode, we explore why ‘weird’ is actually a noun, and how that means that Murphy’s Law can be our friend….

Some years back - more than a quarter-century ago, in fact - one of my publishers sent me a request for, as she put it, “a book for the self-development market that didn’t insult the intelligence”. Looking around at the offerings then available, I could see her point: an awful lot of fluff out there, filled with little more than wishful thinking and a mess of overblown hype about nothing-much. In which case, what would be a good starting-point for an alternative? - that was the obvious challenge there.

Free-will, maybe? - might that be a good place to start? After all, self-guided, deliberate change would not be possible if there were no free-will at all. But against that, there was that old notion of predestination, literally fatalistic: “In the hands of God” and all that. But where did that idea of Fate come from? Hmm…

Turns out that it’s a very old Indo-European myth, about ‘the three sisters of Fate’ in classical Greece, or ‘the three sisters of Destiny’ in the later Roman adaptation of that myth - hence, in turn, the English words ‘fate’ and ‘destiny’. In the Greek myth, the three sisters are Clotho, who spins the thread of each single life; Lachesis, who weaves that life into the fabric of lives; and Atropos - literally, ‘one who cannot be turned’ - who cuts the thread, to bring that life to its end. Definitely fatalistic: no choices there.

Yet is that really there is? Sure, free-will might so often seem like little more like the freedom to make things into even more of a mess than they already were: but there does at least seem to be something that leaves some space for choice and change. So do some digging to see if there were any other versions of the myth.

And yes, there it was, hidden-in-plain-sight in the Nordic tradition: the story of the Norns, who are likewise three sisters, and likewise controlling the passage of our lives. The names are different than the Greek ones, of course: here they’re Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld. Yet unlike the Greek story, here there’s a weird twist in the tale, much like in a Möbius loop:

The first hint of that weirdness is in the name of that first of those three sisters, Urðr - because in Anglo-Saxon, and thence in English, that name is actually pronounced as Weird. And Weird is fate: in an early Anglo-Saxon poem about some battle that I’ve since forgotten, the narrator declaims “Lo, we suffered many dreadful weirds that night!”. The same for the ‘weird sisters’ in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the three witches - yes, they’re weird, all right, but that’s because they’re also ‘the sisters of Weird’, the sisters of Fate. ‘Weird’ isn’t just an adjective: it’s someone’s name.

In that kind of context, ‘weird’ is a noun.

And that one small change changes everything.

As one example, notice what happens to that name ‘Urðr‘ as it moves, over time, into other languages. In English, for example, the hard-’th’ of that ‘ð’-character is hardened to a ‘d’-sound, whilst the ‘u’ is more rounded, to give us the current word ‘weird’. In German, though, the ‘ð’ is again hardened, but without that initial rounding, giving the word ‘erde’ - which then comes back into English as another yet variation of Urðr, this time with the ‘ð’ softened to a soft-‘th’ sound, as the word ‘earth’.

So ‘weird’ is an adjective, and weird is also a noun. ‘Weird’ is fate; fate is also weird. Earth, the place for life, is weird. Life itself is weird.

Weird everywhere. And everywhere is weird. (Or ‘the wyrd’, if you want some distinct way to distinguish the nounal usage from the casual adjective.)

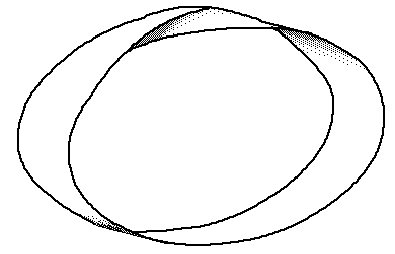

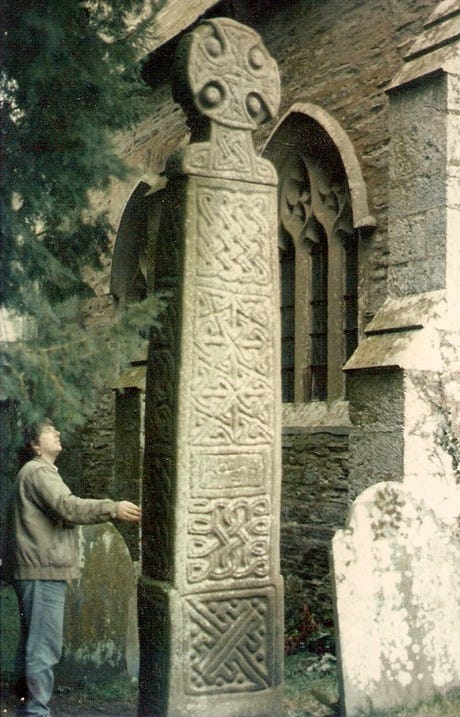

And yes, it gets weirder still. In that Greek myth, the three sisters create a fabric of lives, each life personal, separate, and distinct, linked only by a crosswarp of chance that seemingly still provides no options at all. But in the Nordic form of that same myth, the ‘weird sisters’ create not so much a fabric of lives as a fabric of life - a fabric for life, encapsulating every possibility in life itself. And it’s not the flat fabric implied in Clotho’s name, but more like a vast, infinitely-complex version of a Celtic knotwork, endlessly twisting, turning, looping, dancing through itself:

Sure, a fatalistic life might be like a single lost lonely thread, all but isolated from all others in the Fates’ flat featureless fabric. But a weird life is a much richer one, far more complex, full of choice, jumping each moment from branch to branch across what is actually just one continuous thread of life that is ultimately shared by all. One continuous thread, everything connected, yet also full of twists or turns that loop around and through themselves in unexpected, unpredictable, ever-uncertain ways.

Unlike that fatalistic view, the sisters of Weird tell us that we always have free-will, we always have choice. Yet there’s also always a twist in there somewhere - if only in the ways that our choices bounce off those of others, as in the pinball-like interactions in Brownian motion. There’s always a choice, yet there’s always a twist - and everyone’s life is weird in that way.

Seemingly locked in a loop? - yeah, that’s weird.

Deja-vu and suchlike, that feeling of ‘been here before’? - yeah, that’s also weird.

All those daft stories of reincarnation and the like? - yeah, all of that’s weird too. Of course it is.

Everything is weird, in its own weird way. Weirdness upon weirdness, everywhere.

Weird, right?

But weird isn’t just an adjective, it’s also a noun.

Which means that everything that’s weird in life, well, that’s what weird is.

Life is weird. And weird is life itself. Which means there’s no way out of the weirdness. Sorry about that…

If we fall back to a fatalistic view, that might seem like it’s always a bad thing: “Lo, we suffered many dreadful weirds that night” and all that. Ouch…

Yet there’s another twist in this tale that turns out to be one of the positive, helpful things that we know. And it’s a weird twist on another item that strikes needless fear in every fatalist: Murphy’s Law.

“If something can go wrong, it will” - that’s Murphy’s Law, right? Nothing works; nothing can ever work. Which leads us back into fatalism again…

Wait a minute, though: if Murphy’s Law really is a law, then doesn’t that mean it has to apply to everything? Including itself? Doesn’t that mean that “If Murphy’s Law can go wrong, it will”? So can’t we just ignore that whole Murphy’s Law thing, and be optimistic about everything instead?

Well, maybe it’s not quite that simple - perhaps a bit too deterministic at both of those two extremes? After all, yes, it’s true that some things can and do go wrong, sometimes in very weird ways; yet clearly most things do sort-of work out okay most of the time, too. In which case, both of those views are correct - which, with that phrasing, they can’t be. And there’s also all of that science about uncertainty, too, things like Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems and Schrodinger’s Cat - where does that fit in with Murphy’s Law and the like?

To break of out the paradox, we need to make one small change to that usual phrasing for Murphy’s Law.

Not “If something can go wrong, it will”.

But “If something can go wrong, it probably will”.

Murphy’s Law is only a law because of that uncertainty.

And remember, it’s a law that also has to apply to itself: so if Murphy’s Law can go wrong, it probably will. Which is why most things do sort-of work most of the time in sort-of predictable ways. Sort-of, anyway.

That’s what we might call Inverse Murphy: that things can go right, in unexpected ways.

But hidden in that ‘sort-of’ is yet another weird twist: the more we try to make things more rigidly predictable, the more we suppress that point about ‘probably’, which in turn blocks our access to Inverse Murphy, and forces us back to the bad old days of a Murphy’s Law that only allows things to go wrong, in any or all of those many ways that we don’t expect. Oops…

In which case, the only way we can get Murphy’s Law to work for us, rather than against us, is to embrace its inherent weirdness. Or, in short, if we reframe it like this:

“Things can go right, if we let them - but if we only allow them to go right in expected ways, we’re limiting our chances!”

Weird, right?

But definitely useful…

—-

In case you’re wondering, yes, I did eventually write that book on weird, or wyrd. Two of them in fact. They’re still available in ebook form via Leanpub:

Positively Wyrd: harnessing the chaos in your life (1995) - on wyrd at the personal level

Wyrd Allies: harnessing the chaos in your relationships (1996) - on wyrd at the interpersonal level

I’d intended to make it a trilogy with Wyrd World, on working with wyrd at the transpersonal level, but somehow I never did get round to finishing it. Too many weird distractions, I guess, choices made that took my own wyrd onward into different directions. But might perhaps be useful for me to loop back that way somewhen soon? Your comments on that, if you wish, anyway.

I would submit that "weird" exists between the realms of expected and unexpected in the fabric of society if events do not occur as expected they enter the realm of the unexpected, and are framed by society as "weird" but if the foundation is changed to probable (expected) or unanticipated (unexpected) the results are hailed as insights within a given context. Just weird.