How to avoid slavery

In this episode we explore the underlying drivers behind slavery, and what we can do about it…

Throughout the episodes here, we’ve often explored the challenges and dysfunctions posed by possessionism - the world as seen only through the self-centred eyes of a two-year-old, to whom others exist only as objects or subjects whose supposed sole reason for existence is to serve the self. One outcome of that worldview is the money-based possession-economy, the ‘worst-possible system’ whose inherent structural flaws and failures inherently cripple most people’s lives, and are fast driving us towards a global-scale demise; another is a culture dominated by paediarchy, ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the most childish.

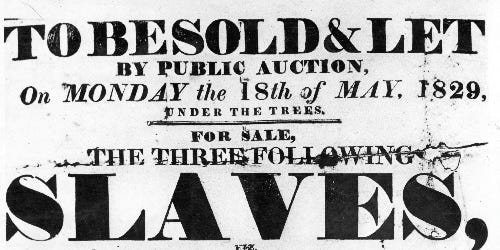

The other key symptom of that ‘eternal two-year old’ is a problem of power. In the physics sense, power is ‘the ability to do work’, which in a human context would be more like ‘the ability to do work, as an expression of personal choice’. But when the two-year-old mindset defines power as ‘the ability to avoid work’, a purported ‘right’ to entrap others into doing the work for them. In a somewhat less-dysfunctional form, that latter definition is how most seem to view the role of machines, as ‘things’ that will do at least of the work on our behalf. But in a context where machines aren’t available, and/or in a possessionist, paediarchal-type culture where others are viewed only as subjects or objects, as ‘things’ that exist only to do our work for us, then what we’re likely to see is this:

There are three main forms of slavery that we need to consider: feudal serfdom, chattel-slavery, and wage-slavery.

Feudal-serfdom occurs within a feudal-hierarchy. Each person is an owned subject of whoever is directly above them in the hierarchy, who in turn is entitled to ‘rights’ of authority and control over the actions and lives of each of their subjects. The monarch or high-priest or suchlike at the top of hierarchy-tree is subject to no-one and has absolute-‘rights’ of authority and control over everyone; by contrast, the serfs at the bottom of the tree are the subjects of everyone above them, and have no ‘rights’ of authority or control over anyone, including themselves. The structure is supposedly justified in that the feudal lord or overseer has a nominal responsibility to provide protection for their subjects, but it’s usually more in the sense of a protection-racket than anything else. In practice, though, the responsibilities are very much one-way: so one-sided as to be slavery in everything but name.

In classic mediaeval feudalism, people are born into their respective ‘station in life’, and those positions are essentially fixed for life; for people at the bottom of the tree, there’s no escape from lifelong servitude to others. There may be a bit more ‘social-mobility’ in post-mediaeval forms of feudalism, such as the führerprinzip of Nazi Germany, or most present-day management-hierarchies, but in practice it’s little better than in the older forms: those who are born rich will somehow be floated ‘naturally’ towards the top of the tree, whilst those born into poverty tend to stay there for the rest of their lives.

Chattel-slavery is the form most commonly understood as ‘slavery’: the person is merely an object, the private property and possession of the owner, without any authority over their own life at all. Chattel-slaves can be bought be bought and sold and exchanged just like any item of property in a possession-economy; and if someone is born into chattel-slavery, they’ll usually remain that way for the entirety of their life. The owner does usually have some responsibilities to the slave, but often only in the same sense as providing the necessary fuel and maintenance for a machine to keep it working: there’ll be no requirement to treat chattel-slaves as people in their own right.

These days, chattel-slavery is supposedly illegal everywhere across the world, but in practice it still definitely exists, in almost every country, in way too many forms. In some cases these may be covered a thin (sometimes very thin…) veneer of legality, such as in for-profit prisons in the US and elsewhere.

Wage-slavery is entrapment in self-servitude, typically via low pay and abusive work-conditions, such as described in the Japanese concept of a ‘black company’ and of karoshi or ‘death by overwork’. The person is nominally ‘free’, but in practice is not; they will have little to no authority or choice within their own lives, especially when at work. The only real difference from chattel-slavery is that the ‘owner’ has almost no responsibility at all: the entrapment occurs because the person is assigned sole-responsibility for their own ‘fuel and maintenance’, but without adequate means to do so, and no feasible means of escape. In effect, the only real choice is between abuse or destitution.

To be blunt, wage-slavery is the status that, to varying degrees of severity, almost all of us live in these days. The risk and the intensity of entrapment is somewhat less extreme in countries that have a some form of universal-healthcare and social safety-net to cover periods periods of illness or unemployment; but even there the entrapment will still be created and maintained by the dysfunctions of the money-economy, such as the literal ‘death-pledge’ represented by a mortgage.

So, how to avoid slavery? The bleak reality is that, under present circumstances, we can’t. It’s an inherent ‘feature’ of the system itself: it’s always going to be there, for almost everyone, to at least some degree, in some form or another.

For example, it might be somewhat cynical though, still painfully accurate, to interpret the US Civil War as a fight about which form of slavery would dominate from then on: chattel-slavery, or wage-slavery. The situation for poor sharecroppers in the South was arguably worse after the end of chattel-slavery, and to a significant extent still is. And the rise of the ‘robber barons’ in the so-called Gilded Age less than 30 years later was only possible because of the way that a possession-economy enables a ‘winner-steals all’ paediarchy, in which a minute minority can indulge in literal life-theft from almost everyone else.

Oh well.

Okay, so how do we get out of this mess?

This answer is straightforward. Whatever form that it takes, slavery is always an outcome of the intersection of three things: a possession-based socioeconomics; a culture in which paediarchy is allowed to run rampant; and a societal concept of power as ‘the ability to avoid work’ rather than the ability to do work as a personal responsibility. Which tells us that the only way to eradicate slavery will be to eradicate all of those three things. We need to replace possession-based economics with a responsibility-based economics. We need to eradicate all of the drivers that underpin paediarchy. And we need to get everyone, from the earliest age, to understand that power is always, and only, the response-ability to do work, not a delusional ‘right’ to avoid work.

That’s it: that’s all that’s needed.

Straightforward and all that. Plenty of real-world examples that point towards that, too: some indigenous cultures, past and present; some religious communities, past and present; some pragmatic social-models such as polder-democracy, and other cooperatives that are not imposed by the state. A lot to learn from there; a lot to do from there.

All straightforward enough - though, uh, yeah, not likely to be easy…

Yet that’s how to avoid slavery: if we want slavery to end, that’s the only way in which that could at last become possible.

So that’s the task, right there. Let’s get to it, shall we? - for everyone’s sake, including our own?