In this episode we explore why ‘intellectual property’ seems essential in a money-economy, yet is destructively irrelevant for anything else.

Who owns an idea? Why is it so important that they should? And even more, why they should not?

None of this is as simple as it seems, yet ultimately all of the answers to those questions become patently obvious. Literally so.

The reality is that it’s a mess. Like everything else in the possession-economy, it’s a mess. What’s perhaps surprising is just how long this mess has been going on: for patents, it’s almost five hundred years, and for copyrights it’s not quite four hundred. But being old doesn’t make it better: it’s just an older mess than we might have expected, that’s all…

So what’s the real background here? It\s a combination of two different issues, both of which arise only in a possession-economy, but have significantly different aims.

The first is that a possession-economy only works properly with physical ‘stuff’, because it depends being able to exchange things but also control or prevent access to them. It needs things to be ‘alienable’: if I give it to you, I no longer have it, but you have to pay me first. The catch is that it doesn’t work that way with ideas or information: for those, if I give it to you, I still have it (‘non-alienable’), but I also can’t stop you creating as many copies as you like to give or sell to someone else. The only way that we can sort-of kludge a possession-economics to sort-of work with ideas and information is to declare them to be ‘intellectual property’: we pretend that they’re physical, even though they aren’t. That’s essential within a money-based possession-economy, because that’s the only way that someone who produces ideas or information can have a ‘product’ that they can sell, and hence make some kind of living from their product.

People who work with ideas and information - analysts, artists, inventors and more - get paid to produce that information. Sounds fair, right? Well, it would be, if it actually worked - which, all too often, it actually doesn’t, and actually can’t.

We have a problem…

Back in the past, we could sort-of pretend that it sort-of worked, by embedding the idea or information into a bundle with something physical, so as to make it accessible only via some excludable form: bundle a story into a printed book, a song into a songsheet or a disk, a film shown within a cinema. But the moment the package gets de-bundled - such as trying to save costs by going ‘all-digital’ - then that form of protection vanishes. And the result is that there’s once again no way for the creator to claim the ‘rights’ to get paid. Oops…

Even worse, the creator’s purported ‘rights of possession’ can easily become hijacked by someone else. Employees often discover this one the hard way: for example, as an employee in a medical research-lab, my mother developed a way to use a knitting-needle gauge to measure the size of nerve-fibres - but her boss not only claimed the credit for all of her work, but also was awarded the patent, and all the income that came from the process and its derivatives. Some employers claim to ‘possess’ all such rights not only from employees’ time at work, but also the entirety of their life away from work, and even when they’ve left the company - a situation which has triggered lawsuits between employers each claiming absolute rights over the product of the entirety of an employee’s past, present or future life.

It’s a mess…

What we then get is an even worse mess, with the purported possessor of that ‘intellectual property’ attempting either ‘rent-seeking’ - charging others a fee for the use of their purported ‘property’ - or else preventing anyone else from using it - such as to assign themselves an exclusive monopoly over an entire market. Which often forces people to do waste further time and effort on inventing alternatives, not for any direct value as such, but solely in order to find a way to bypass the blockade or the rent-seeking.

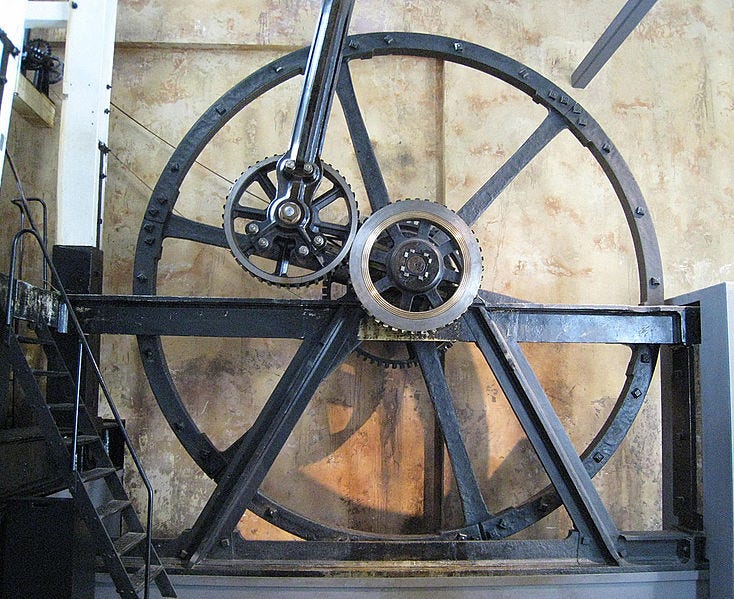

And, of course, we’ll often see ‘innovations’ that exist solely to bypass some ‘property-holder’s block or rent-seeking, and perhaps also for the purpose of creating their own block or rent-seeking - all of which is built upon ideas that have been stolen from someone in the first place. Layer upon layer of this, sometimes. One classic example of that would be the ‘sun-and-planet’ gear, a device used in early steam-engines to convert linear motion to rotary motion:

To quote the Wikipedia article:

It was invented by the Scottish engineer William Murdoch, an employee of Boulton and Watt, but was patented by James Watt in October 1781. It was invented to bypass the patent on the crank, already held by James Pickard.

So, to translate:

the obvious device for the requirement was the crankshaft

James Pickard had obtained a patent for the crankshaft - despite the fact that by then it had already been in common use for several centuries - and he then used that patent to try to prevent anyone else from building a steam-engine that required rotary motion, so as to keep that market to himself

William Murdoch was tasked by James Watt to invent an alternative means to do the same task, and he selfsucceeded in doing so - although his sun-and-planet gear was more complex, more expensive to build and somewhat less efficient than the much simpler crankshaft

Boulton and Watt used Murdoch’s invention to bypass Pickard’s patent

although the work had actually been done by Murdoch, James Watt claimed the patent for it, giving him the sole right to possess and profit from it

Boulton and Watt used the patent on the sun-and-planet gear to try to prevent others from making steam-engines with any rotary output

being wasteful and inefficient, the whole system of sun-and-planet gear was abandoned just ten years later, as soon as Pickard’s crankshaft-patent expired

Yeah, it’s a mess. And the entire patent-system is getting worse and worse in that way with each passing year…

But wait a minute, you might ask - where exactly do ideas come from in the first place? The short-answer is that we don’t know. In fact one of the few things we do know about it is that, as per scientists such as physicist David Bohm, ideas and innovation are always social, arising at least in part from interactions between multiple people.

Yet if that’s the case, how can one person honestly claim to be the sole creator, and thence claim exclusive possession of that ‘intellectual property’? Short-answer: we can’t. Not in any honesty. Oops…

In short, it’s patently obvious now that the whole concept of patents and the like is completely broken. Worse than broken: by definition, it’s inherently based on some form of theft - in many cases, layer upon layer of unacknowledged theft.

Not exactly a great basis for an entire economy…

If we’re honest about it, the only good thing we could days about ‘intellectual property’ and the like is that in some cases it provides a means for some people to somehow do something resembling ‘making a living’ within the dysfunctional mess of the money-based possession-economy. That’s it: that’s all there is. Beyond that, it adds no real value at all: it fails almost completely in its nominal purpose of making innovations and ideas patently obvious and available to everyone. All it really does is waste energy and effort, and slow everything down. Wow…

So what can we do about it? Short-answer: just get rid of the whole miserable mess. Get rid of it: gone. Most of it’s based on parasitic paediarchy anyway, which is never a good thing to protect. The only people who might have any honest reason to need its existence are the real creators - and even that ‘need’ itself becomes irrelevant once we dismantle the mess of the possession-economy, and replace it with a more humane, viable and sustainable responsibility-based economy, much as I’ve described in previous episodes here.

Get rid of ‘intellectual property’? Not a small change, of course - but then almost none of this is. Yet every big change is made up of a myriad of smaller changes - and if we plan and enact them right, each small change can help in some way towards freeing our lives from the poisonous pointlessness of the possession-economy. That’d be one change that would make things much better for us all.

Many employment contracts now contain intellectual property clauses which in many cases stifles innovative thought within the company, why would an individual utilise his / her grey matter to introduce a concept which only benefits senior management and shareholders, when they can leave start their own company and claim full IP rights for themselves. Seems counter productive to keep this archaic nonsense around if we are to build a sustainable future.

Would we see mobile phone operators as IP thieves when the original IP would have been reliant on Mr Alexander Graham Bell as the thought leader for communication devices?

Interesting as always Tom.